“If you don’t make a credible case, you’re not going to get the water,” Water Commissioner Aurora Kagawa-Viviani said November 18 of the permit applications submitted two years ago for water from the streams and aquifers of West Maui, also known as Maui Komohana.

That day, the state Commission on Water Resource Management received a staff briefing summarizing the existing water use permit applications for the public and privately owned water systems that provide most of the water in the region.

Among other things, commission deputy director Ciara Kahahane and staff hydrologist Ayron Strauch, who authored the report, described the hundreds of rather incredible existing water use claims for single family residences.

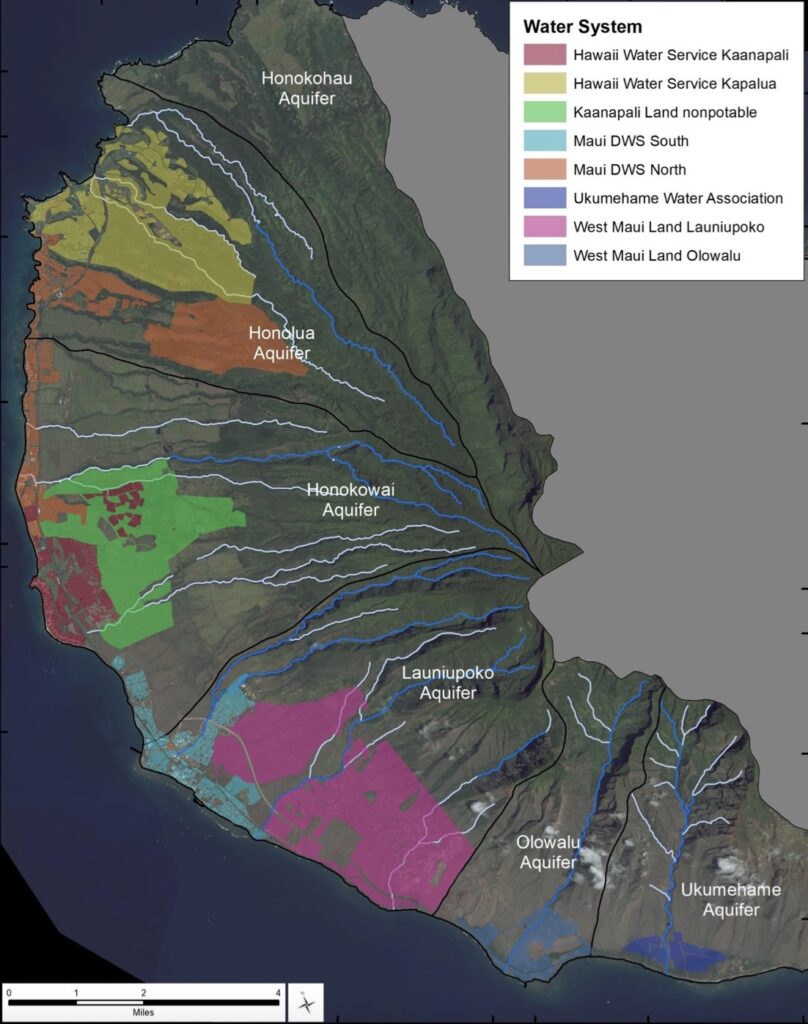

In response to the Water Commission’s June 2022 designation of the Lahaina aquifer sector as a ground- and surface-water management area, the agency received over the next year or so 93 applications for existing uses and 48 applications for new uses of water.

According to commission staff, none of those applications are complete. And so none have been published in a local newspaper, as required under the state Water Code. Publication would start the clock ticking on when objections to any applications have to be filed and when the commission must make a determination on the applications.

Under the code, the commission has 90 days to act on an application that does not require a hearing and 180 days to act on an application that requires one.

Applications that may not require a hearing are those that seek no more than 25,000 gallons per month (slightly more than 800 gallons a day) or those where the applicant seeks more than that but no one with standing to file an objection does so. Should someone with standing file an objection within ten working days of the last public notice of a permit application, a hearing would be required.

Commission staff did not delve very deeply into the deficiencies that are preventing the applications from being deemed complete.

According to a report to the commission on April 28, staff began processing in December 2023 the applications for both existing and new uses in the Honokōwai sector, which is arguably the most strapped system in the region. But letters requesting more information from the Honokōwai applicants were not mailed until July 2024, the report noted.

At the commission’s November 18 meeting, staff reported that they are still seeking information from applicants.

This revelation did not sit well with Honokōhau Valley farmer and water use applicant Karyn Kanekoa.

“We kalo farmers, we’re experiencing a lot of taro rot. In some cases, over 60 percent of the patches are rotten and this is mainly because of the warmer water temperatures, and why is that? Less water in the stream.

“I’m trying to keep my composure cuz I’m super fricken irritated to hear that none of the applications are complete. Like, how come it took two years to tell us that? And if our applications are incomplete, then how come staff hasn’t sent us a letter on what’s incomplete? Come on, hurry up. … We want to get our permits approved.

“And what’s even more frustrating to me is, and insulting, is that, actually, we’re just being dragged along with this process, because the Water Code says that our water use permit applications for kuleana shall be granted upon submission [Hawaiʻi Revised Statutes Ch. §174C-63]. We submitted our applications two years ago, so what’s the deal? What’s going on? How come?”

Other members of the public voiced similar complaints.

Kahahane had suggested back in April that the commission should deal with the surface water use permits for Honokōhau, where interim instream flow standards have been set and many of the applications are for traditional and customary practices, and with the groundwater permits for Honokōwai, where amounts requested in the applications submitted exceed the aquifer’s sustainable yield of 6 million gallons a day.

In issuing the permits for the different regions, Kahahane suggested that the commission start with applicants who have appurtenant (kuleana) and traditional and customary rights, then take up permits for municipal and other public trust uses, mainly domestic uses, followed by other existing uses.

She also suggested that the commission could issue interim permits in the meantime. The Water Code states that the commission “shall” issue an interim permit for existing, reasonable and beneficial uses and for an “estimated, initial allocation of water if the quantity of water consumed under the existing use is not immediately verifiable.”

She noted that the commission has not always issued interim permits before final ones. But according to her April 28 power point presentation, interim permits in this case would allow for faster changes to the status quo, the reduction of excessive water use, and an assessment of alternative sources “sooner than later.”

‘Egregious’ Uses?

Whether or not the commission decides to issue interim permits, it was clear from last month’s briefing by Kahahane and Strauch that the existing water use claims may not be credible or may fail to meet the reasonable-beneficial standard required by the Water Code.

Individual homeowners whose water use has been included in applications submitted by one of the large purveyors have already argued the amounts are off. (See our report on the stated water use of lots in just one Kapalua subdivision, elsewhere in this issue.)

Kahahane made it clear at last month’s meeting that the summary report was just a first look at the applications.

“This analysis is only as good as the data it was based on. Those data came from the applications,” she said, adding that the report was not intended to be a verification of those applications.

A review of the existing-use applications published on the commission’s website shows that they often include default values for water requirements (e.g. 600 gallons per day per household or 3,400 gallons per acre per day for diversified agriculture), even for vacant house lots or fallow ag lots.

For instance, the Water Commission’s recent permit summary touches on the water use application submitted by the Kaʻanapali Land Management Corporation for Honokōwai groundwater. The company, the report states, “did not report any metered end use. All values reported are estimates based on calculated water demands by plants and animals, not metered water delivered. Kaʻanapali Land Management uses an estimated 3.036 [million gallons a day, or mgd] for diversified agriculture, including 2.302 mgd for coffee, banana, dryland kalo, papaya, and other row crops and 0.712 mgd for livestock irrigation and crop processing. In addition to diversified agriculture, Kaʻanapali Coffee Estates is a luxury agricultural estate development that utilizes non-potable water for coffee and landscape irrigation on the subdivided parcels.”

KLM’s estimated water demand for landscape irrigation was 2,300 gallons per acre per day. Its estimated demand for coffee and citrus orchards was 5,819 gallons per day. This is more than twice the amount that Dr. Ali Fares, a crop irrigation expert, has estimated is needed for Mahi Pono’s coffee crops in Central Maui. In an August 2024 report on irrigation requirements estimates, he wrote, “On average, coffee crops use 2,583 gallons per acre [GAD] per day, a slightly higher rate than the 2,536 GAD of the citrus.”

KLM’s application, however, justifies its higher rates. “The water use application rates were established with many years of experience in growing coffee orchards to maximize crop yields,” it states.

And then there’s the August 2023 groundwater use permit application submitted by the Ukumehame Water Association, Inc., for what aerial photos from 2023 show are largely undeveloped and unfarmed agricultural lots.

Only three of the 11 lots with claimed existing uses grow any crops. One eight-acre lot reportedly growing sod has structures, but no county-recognized farm dwellings. Still, it claims an average potable water consumption of 25,444 gallons a day with non-potable consumption of 19,075 gallons a day.

Another lot has no crops, no landscaping, and no houses, yet has a claimed average daily use of potable water of 1,729 gallons. Another with a house but no crops is identified in tax records as non-owner occupied/residential, and has claimed average daily potable use of 5,452 gallons.

According to Strauch, about ten percent of the single-family dwelling lots listed in the permit applications claim to use more than 2,000 gallons of water per day.

Three-hundred-fifty-eight in total, Kahahane said.

“This begs the question, what is a reasonable use for a single-family dwelling?” Strauch added.

Kahahane reported that water use by single-family dwellings by far outstrips that of other uses, such as hotels and resorts.

Strauch suggested that if the commission were to limit all single-family dwellings in the applications to about 2,000 gallon per day, it would save 2.3 million gallons a day.

Commission chair Dawn Chang pointed out that the average reported use by single family dwellings in the sector was less than 1,000 gallons per day. “But you’re being generous with 2,000,” she said.

“We’re being generous,” Kahahane replied.

Strauch said most of the single-family dwellings listed in the permit applications reportedly use less than a thousand gallons per day, “a very reasonable amount.”

“The county system standard is 600 gallons per day. And even at a thousand gallons per day, this might represent multi-generational housing, accessory dwelling units that are combined, but not separated. It’s the egregious end use at the top end of the spectrum that is of concern,” he said.

But first, the applications need to be deemed complete. Kahahane said the name and address boxes need to be filled in, instructions followed, and the application must be internally consistent. “We probably would not accept an application where box 1 and box 2 did not equal box 3 if they were supposed to,” she said.

“Once it was complete to our satisfaction, that’s when we would deem it to be accepted. From there, we have to do this other step of verification. … If they claimed 5,000 gallons of water a day and we look at the satellite data and it doesn’t look like they’re using 5,000 a gallons of water a day, that goes to the verification process rather than acceptance,” she said.

“I think we’re studying this thing too much,” commissioner Lawrence Miike later said. “After all, the burden is on the applicant to show existing use. You gotta justify it. I suggest our emphasis be on all of the applicants completing their applications to the satisfaction of the commission.”

He added, “I agree with whoever said we should start with the small applicants. … We really need to start approving water use permit applications.”

Commissioner Kagawa-Viviani commented on the complaints about how slow the process has been.

“We are slow, but when the applications came in … there was an awareness that staff didn’t want to reach our right after the [Lahaina] fire. Right now we’re dealing with it. I don’t want to make excuses, but that was some of the intention. But it’s clear we need to communicate with the applicants on what’s missing,” she said.

She also said applicants need to know “what bars they need to clear,” referring to the Water Code’s requirement that applicants must establish that their proposed use of water “(1) can be accommodated with the available water source; (2) is a reasonable-beneficial use…; (3) will not interfere with any existing legal use of water; (4) is consistent with the public interest; (5) is consistent with state and county general plans and land use designations; (6) is consistent with county land use plans and policies; and (7) will not interfere with the rights of the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands.”

Also, the code allows the commission to suspend or revoke a permit if it finds the application contained a materially false statement.

— Teresa Dawson

Jim McMahon

According to the EPA, the average family in the US uses 300 gallons of water per day. My wife and I are on a farm with 3 cows and a small 600 sqft. greenhoouse. Our average daily use is only ~200 gallons. So yes, anything over 1000 gallons per day would seem to be generous.