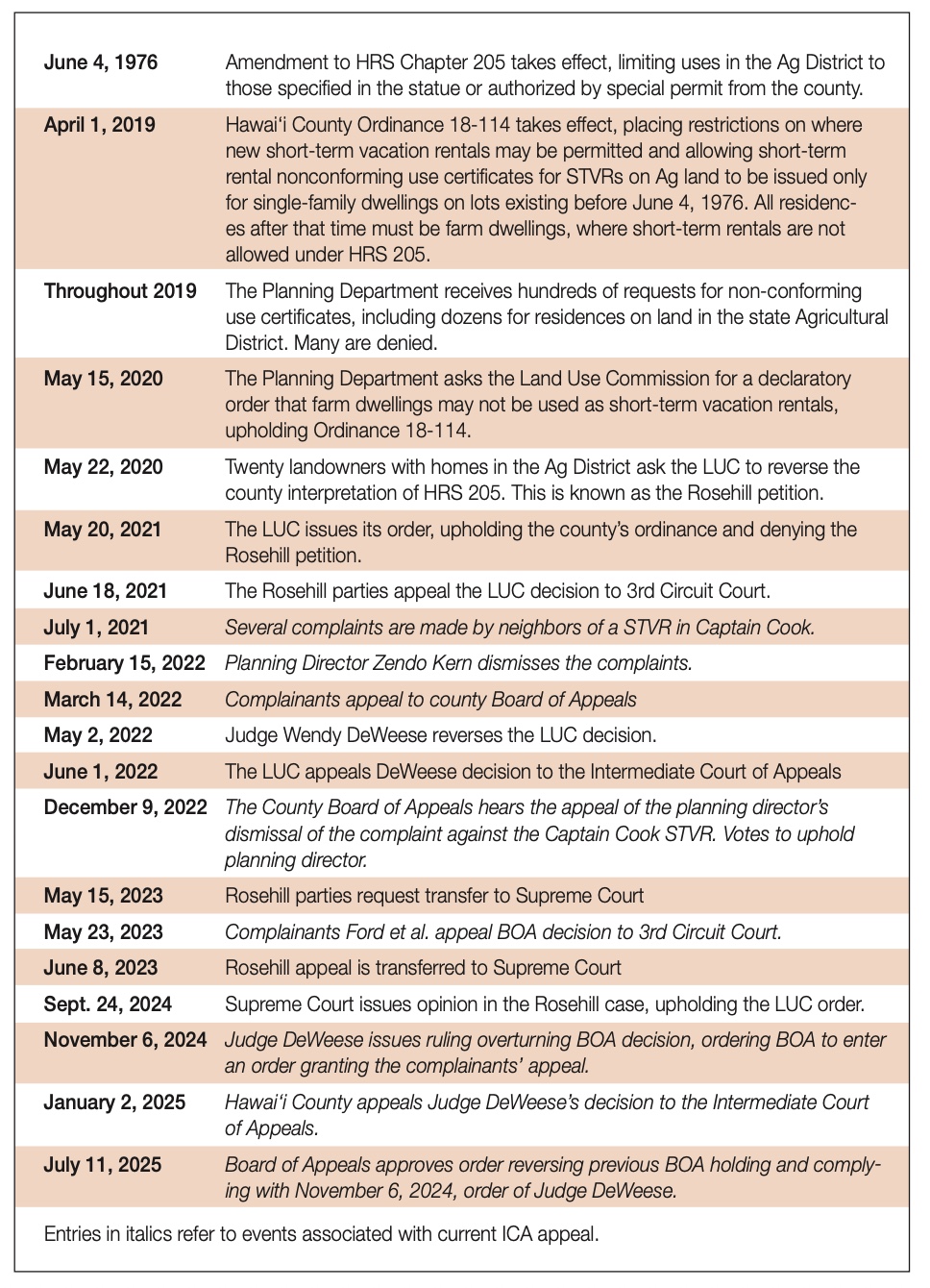

More than a year ago – September 2024 – the state Supreme Court issued a ruling on the question of whether short-term vacation rentals are allowed on land in the state Agricultural District.

The answer was a resounding no.

The issue before the court arose in Hawaiʻi County, following the county Planning Department’s denial of permits to operate STVRs to more than a dozen owners of Ag land. Many if not most of the owners had been renting or planned to rent out houses on their Ag land to tourists.

After years of litigation, involving lower court action and a finding by the Land Use Commission that such uses are not allowed under Chapter 205 of Hawaiʻi Revised Statutes, the high court upheld the finding of the LUC – to wit, that “farm dwellings may not be used as short-term vacation rentals under HRS Chapter 205.”

There was no quibble about whether the rentals were “hosted” (with an owner or manager on site) or “unhosted,” or the length of time that qualified as short-term. Nor did the court qualify its ruling by limiting the applicability of its prohibition to one or another specific section within Chapter 205.

Yet now county attorneys profess to be confused by the ruling and the Planning Department is allowing “hosted” vacation rentals to continue to operate in the Agricultural District, claiming that the Supreme Court decision was actually much narrower than it would seem at first glance. And the county is defending that claim in a case pending before the Intermediate Court of Appeals.

Background

The case goes back to a decision in 2021 by then-county Planning Director Zendo Kern. Several people owning lots in a county-designated Agricultural Project District near the South Kona village of Captain Cook complained in July of that year that Ryan Neal and Beata Zanone, owners of a five-acre lot in the same project district, were operating a short-term vacation rental without a permit, on Ag land, and in violation of the covenants, conditions, and restrictions on the property.

The complaints came nearly a year after the state Land Use Commission had issued its declaratory order that short-term vacation rentals in the state Agricultural District are not a permitted use under Chapter 205 and that the “residential use of a farm dwelling without any connection to an agricultural use has never been allowed in the Agricultural District.” The order upheld the position of Hawaiʻi County, which had been challenged by owners of Ag lots carved out after June 4, 1976. That’s the date a state law limiting residences on Ag land to farm dwellings took effect.

Both the county and the landowners seeking to rent out homes on their Ag land appealed the LUC’s decision to the 3rd Circuit Court of Judge Wendy DeWeese.

This was the legal landscape concerning vacation rentals in July 2021, at the time the complaints against Neal and Zanone were lodged.

Appeals on Two Fronts

In September, Kern sent a “warning letter” to Neal and Zanone, informing them that the Planning Department had received a complaint about their operation. He went on to recite the conditions under which short-term vacation rentals could be permitted, referring to an ordinance passed in 2018. “Your property … is located on county Agricultural Project District (APD) zoning district and State Land Use Agricultural (A) zoning district,” he wrote. “Please take this opportunity to address the use of this property and come into compliance with the new law within 30 days.”

On October 12, Patrick Wong, attorney for Neal and Zanone, responded to Kern. His clients were not operating a short-term vacation rental, he stated, because “Planning Department Rule 23-3 provides that a ‘Short-Term Vacation Rental’ means ‘a dwelling unit of which the owner or operator does not reside on the building site …’ It is our understanding that a portion of the entire dwelling may be rented on a short- or long-term basis as a hosted rental, provided the owner or operator resides on the property.” (All emphasis was added by Wong.)

Wong went on to say that “fee owner Neal is a full-time resident of the property, Zanone is more than a half-time resident of the property, neither operate a STVR operation on the property … and on occasion [they] may host guests on the property as a hosted short- or long-term rental, in compliance with all applicable rules and regulations.”

A print-out of an on-line advertisement provided to the Planning Department describes the property as consisting of “three villas on a private, beautiful 5-acre fruit orchard retreat.” The villas are “inter-connected, yet private … all with large sliding glass door openings onto a shared courtyard, pool and patio.”

“Currently, one of the villas is occupied by owner,” the ad goes on to say. “He will assist with providing keys and is available if needed.”

Nine days later, Kern replied: “Planning has received your letter … and were able to confirm that your clients are not operating a Short-Term Vacation Rental. We appreciate your cooperation in resolving the above-mentioned complaint and consider this case closed.”

Instead of informing the complainants directly that their complaints were meritless, the Planning Department merely sent them copies of the letter to Wong.

On January 20, 2022, attorney Michael Matsukawa, representing several of the complainants, informed Kern that his letter to Wong did not suffice to resolve the complaints. “As you know,” Matsukawa wrote, “without a final decision, your ruling is not final and can always be revised. Further, the complainants cannot file an appeal to the County of Hawaiʻi Board of Appeals until they receive a letter ruling on their complaints.”

Matsukawa also noted that Kern’s letter “did not address the issue that the complainants raised, which issue was the focus of the State Land Use Commission’s declaratory order … and the focus of the State Legislature in Act 77, … effective July 1, 2021.”( Act 77, recommended by the Office of Planning, changed the language of 205 with respect to uses of farm dwellings to state that they had to be “accessory to” farming activity, rather than used “in connection with.”)

He quoted the language of the declaratory order, which found that “Purely residential uses, with no connection to an agricultural use, … have never been allowed in the Agricultural District” and “A STVR is not a permitted use of a farm dwelling in the Agricultural District under HRS Chapter 205.”

Also, “a single-family dwelling can be defined as a farm dwelling only if the dwelling is used in connection with a farm where agricultural activity provides income to the family occupying the dwelling” and “a single-family dwelling which use is accessory to an agricultural activity for personal consumption and use only, is not permissible within the Land Use Agricultural District.”

Kern then issued letters to all complainants on February 15, formally notifying them of his decision. He referred to the county zoning code, which defines farm dwelling as “a single-family dwelling located on or used in connection with a farm, or if the agricultural activity provides income to the family occupying the dwelling.” The code also defines short-term vacation rental as a “dwelling unit of which the owner or operator does not reside on the building site, that has no more than five bedrooms for rent on the building site and is rented for a period of thirty consecutive days or less.”

Based on those definitions, Kern said, “the parcel in question is not in violation” of the county code. “This case is now closed.”

On March 14, Matsukawa filed an appeal on behalf of six neighbors, all owners of lots in the same agricultural subdivision, asking the county Board of Appeals to overturn Kern’s finding. He pointed out that the lots were created after June 4, 1976, and are thus subject to all of the requirements of Chapter 205 and the LUC’s determinations of its applicability.

“The question presented is not whether transient rental activity is ‘hosted’ or ‘non-hosted’ activity,’” he wrote, “but whether such activity complies with Chapter 205, HRS, and the determinations of the Land Use Commission.”

Less than two months after Matsukawa filed the appeal, Judge DeWeese issued her ruling in the Circuit Court appeal of the Land Use Commission’s declaratory order strictly limiting the use of residences on lots in the state Agricultural District.

DeWeese found that the LUC’s order was in error, in that it had concluded that a short-term vacation rental, as defined by the county, could never be a farm dwelling, as defined by statute. A comparison of the county ordinance relating to short-term rentals with Chapter 205 “reveals that a dwelling may simultaneously meet the definition of a ‘farm dwelling’ pursuant to HRS Chapter 205 and the county’s definition of ‘short-term vacation rental,’” DeWeese wrote.

The Land Use Commission at once filed an appeal of her ruling to the Intermediate Court of Appeals. That appeal was still pending at the time the county Board of Appeals took up the case brought by the neighbors of Zanone and Ryan.

The Board of Appeals

After several continuances, the Board of Appeals was scheduled to hear the case involving the Ryan-Zanone property at its October 2022 meeting.

Wong, attorney for the couple, filed a motion for summary judgment on September 30, arguing that the county code did not prevent the use of homes in the state Agricultural District as hosted short-term vacation rentals. He cited the ruling by DeWeese, which overturned the LUC’s declaratory order.

In response, Matsukawa objected to Wong’s filing, noting that nothing in the Board of Appeals’ rules allowed it to consider motions for summary judgment.

Aside from that, Matsukawa described the issue on appeal not as the use of the Zanone-Neal property as a bed-and-breakfast operation. Rather, it was the fact that the operation was ongoing without the required county permit and, in addition, violated conditions of the county ordinance establishing the agricultural project district that prohibited commercial operations.

On December 9, 2022, the BOA finally heard the appeal.

In arguing in support of his motion for summary judgment, Wong stated that the complaint “speaks to and asks the director to apply state law and also to apply a Land Use Commission decision which we all know has been overturned by Judge DeWeese and is pending current review at the appellate level.

“If the underlying complaints can cite to the Land Use Commission decision, then so too can we rely upon what the current state of the law is in this jurisdiction, as rendered by Judge DeWeese. … There is no application of the short-term rental ordinance to my client. … There’s no violation of that statute.”

In response, Matsukawa repeated his position that the Board of Appeals has no rule allowing it to consider motions for summary judgment. “It’s like asking an appellate court that’s hearing an appeal to render a summary termination of the appeal based on some motion and argument. The appeal is to consider all the issues.”

As to the case decided by Judge DeWeese, Matsukawa said it had nothing to do with the appeal of his clients. “If you read that decision, it makes clear that none of the parties in the Rosehill case have properties that were set apart as a special county Agricultural Project District.” (Linda A. Rosehill was the first of more than a dozen owners of land in the state Agricultural District who challenged the county’s ordinance banning short-term vacation rentals on Ag lots created after June 4, 1976, the date that amendments to Chapter 205 took effect, banning all uses in the Ag District unless they were specifically permitted in the statute or allowed under special permits.)

“The properties in this case all were put into the county Agricultural Project District per county Ordinance 97-133. That is the governing standard. …The planning director did not address the question of what uses are allowed within a county Agricultural Project District.”

In reply, Wong seemed to agree that Rosehill didn’t apply. Then he added, “We also know the Planning Department is working quite diligently on rules that deal with hosted rentals. It’s not before you yet, but you’ll see it. … Once those rules are adopted and my clients apply for and secure their permit under those rules that are currently not in effect, and there’s a violation then, I think then it would be more prudent for the neighbors and the appellants to raise those issues. Currently, there is no violation.”

After a lengthy executive session, the board voted to uphold the planning director’s dismissal of the complaints, accepting Wong’s motion for summary judgment. Wong was also asked by the board to prepare the final order, which the board approved in April 2024.

On May 23, Matsukawa, representing six of the petitioners, appealed the decision to 3rd Circuit Court. Hearing the case was, once more, Judge Wendy DeWeese.

Action in the Courts

As mentioned earlier, DeWeese’s order in Rosehill was appealed to the Intermediate Court of Appeals in June 2022. A year later, in June 2023, it was transferred to the Supreme Court, in keeping with the court’s decision earlier in the year that held appeals from LUC declaratory orders should be brought directly before the high court.

So, at the time Matsukawa appealed the BOA decision, Rosehill had been before the Supreme Court for nearly a year. In fact, oral arguments had already been heard by the court, on May 16.

On September 24, 2024, the Supreme Court issued its opinion, authored by Chief Justice Mark Recktenwald. Because, in the light of intervening court rulings, the case should not have been brought before the Circuit Court in the first place, the high court stated that the decision of DeWeese had no weight. Still, the Supreme Court’s analysis of the arguments that DeWeese found persuasive was pretty devastating.

The upshot was that, on November 7, DeWeese had to take notice of the high court’s finding that “short-term vacation rental activity, which is a form of transient accommodation, is not a direct permitted use in the state Land Use Agriculture [sic] District. … As such, the Hawaiʻi Supreme Court’s decision in Rosehill resolves the main issue that is raised in the agency appeal that is now before this court.” (This despite the fact that both Wong and Matsukawa maintained that the question before the BOA had nothing to do with Rosehill.)

Still, DeWeese wrote, there were outstanding questions that needed to be resolved: “(1) whether the Hawaiʻi County Board of Appeals used an unauthorized procedure; (2) whether the board met in an unauthorized executive session, (3) whether the board failed to render written findings and conclusions to support its orders, and (4) whether the board ignored the pre-Rosehill decision of the 5th Circuit Court in the ‘Campos Case’ that transient accommodation activity is not a direct permitted use in the state Land Use Agriculture District. The answer to each of these questions is ‘Yes.’”

At the conclusion of her 36-page order, DeWeese vacated the BOA’s decision and ordered it to grant the appeals requested by the original complainants.

Zanone and Ryan then appealed the ruling to the Intermediate Court of Appeals, where it is pending. The county separately appealed. In July, the ICA joined the two cases.

After months of continuances, the Board of Appeals finally approved the order carrying out DeWeese’s orders at its July 2025 meeting. While approval was perfunctory, one of the complainants, Robert Gage, suggested that the reason behind the delays was the hope that the Intermediate Court of Appeals might issue a decision favorable to the county before the BOA carried out DeWeese’s order. The county attorney denied this, saying the delays were merely the result of administrative issues.

Meanwhile, Before the ICA

As mentioned, litigation over the county’s efforts to regulate transient rentals on land in the Agricultural District continues in the Intermediate Court of Appeals, with the county now agreeing with Zanone and Ryan that the Supreme Court’s decision in Rosehill did not absolutely prevent short-term rentals of dwellings in the district. Rather, it only applied to unhosted rentals. The basis for the claim, the county says, is the fact that the Rosehill petitioners challenged the county Ordinance 18-14, which defined short-term vacation rentals as referring only to unhosted rentals, specifically, “a dwelling unit of which the owner or operator does not reside on the building site.”

While the complaining neighbors “strenuously argue HRS Chapter 205, Rosehill, and Campos restrict all forms of transient accommodation activity on the state Land Use Agriculture District, this is clearly not the case,” the county says in a reply brief filed with the ICA in July.

As for the short-term vacation rental rules, which the county had indicated would be in place soon in the December 2022 Board of Appeals hearing, they’re still a work in progress.

In June, the Hawaiʻi County Council passed Bill 47, which became Ordinance 25-50, that added a section to the County Code addressing transient vacation rentals. The ordinance, set to take effect next spring, defines a TVR as “a dwelling, dwelling unit, room, apartment, suite, shelter, or the like: that is, or is offered to be, furnished and rented to a transient for a rental period of less than one hundred and eighty consecutive days and in exchange for money, goods, services, or other consideration.” It excludes hotels, motels, inns, apartment hotels, boarding facilities, lodges, timeshares, and tents.

The ordinance also distinguishes between “hosted” TVRs, which are “located on a property that is the principal home of a host, and “unhosted,” located on a property on which a host does not reside while the TVR is rented.

Administration of the law is given over to the Finance Department. The only reference to the state Land Use Law is oblique. “Notwithstanding any provision to the contrary, a short-term vacation registered … prior to the effective date of this ordinance is deemed separately registered.”

In other words, short-term vacation rentals are not addressed at all in Ordinance 25-50, which amends Chapter 6 of the County Code. Rather, they are defined only in Chapter 25: “‘Short-term vacation rental’ means a dwelling unit of which the owner or operator does not reside on the building site, that has no more than five bedrooms for rent on the building site, and is rented for a period of thirty consecutive days or less.” It goes on to exclude “the short-term use of an owner’s primary residence,” as defined by Section 121 of the Internal Revenue Code.

Regulation of STVRs appears in Section 25-4-16 of the zoning law, added after the passage of Ordinance 18-114. This strictly delimits the zones in which they may be permitted, restricting them to urban centers and resort areas, generally, and requiring them to be registered with the Planning Department. Pre-existing STVRs outside of the designated areas were allowed to register as non-conforming uses, subject to annual renewals.

Passage of this law was what triggered the Rosehill petition, specifically the provision stating, “In the state land use district, a short-term vacation rental nonconforming use certificate may only be issued for single-family dwellings on lots existing before June 4, 1976.”

Notwithstanding the ongoing litigation, the county Planning Department continues to allow short-term “hosted” operations in the state Agricultural District. In defense of this, it has stated that “renting a stay on one’s property is not per se prohibited within the state Land Use Agriculture [sic] District if it is ‘compatible to the activities described in section 205-2 as determined by the commission.’” The only residential uses allowed in that section are farm dwellings and employee housing.

Yet the county’s zoning code lists many more uses that may be allowed in the Agricultural District if they receive a special permit. These include adult day care homes, nursing and rest homes, bed-and-breakfast establishments, family child-care homes, guest ranches, lodges, and model homes. A “guest ranch” is defined as an operation that “offers recreational facilities for activities such as riding, swimming, and hiking, and living accommodations.” A lodge is “a building or group of buildings … containing transient lodging accommodations without individual kitchen facilities, and no more than forty guest rooms or suites, and generally located in agricultural, rural, or other less populated areas.”

— Patricia Tummons

Phillip Koszarek

Thank you for highlighting the county’s effort to allow vacation rentals in Agricultural Districts. I am one of the neighbors negatively impacted by the county’s decisions and behavior.

The first question is who in the County was making this decision. Zendo Kern was the primary person. The Mayor was in on it. When I contacted the Mayor’s office the response was “Mr. Kern’s policies are the policies of the Roth Administration”. The legal staff was totally committed and defending Kern. When I contacted the County Council they implied they were not involved. They said something like “its complicated”. It wasn’t complicated. So essentially we know the entire County administration was behind the effort to allow vacation rentals in Ag Districts and the County Council was non-committal.

The next question is why. We know very little as the County does not give reasons for their actions. We were told the County made a decision to only enforce Ordinance No. 18-114. If you review the correspondence you can see this is what they did and totally ignored State Law.

Let’s do a quick review of some actions by the Zendo Kern and the Roth Administration.

Zendo Kern took our original complaint and changed it to say the landowner was in violation of County Ordinance No. 18-114. The big problem here is that Ordinance No. 18-114 does not apply to the property. Yes, that is a fact. The Planning Director told the landowner he was in violation of an ordinance that did not apply to him. Which of course made it very easy for Zendo to close the case without ever acting on the actual complaint. I would like to note that Mr. Kern was never willing to admit the mistake and continued to publish more absurd statements.

We took our case to the County Board of Appeals and were denied a full hearing. We appealed to the Third Circuit Court. As you documented the Court said the County “used an unlawful procedure and held an unlawful executive meeting”. The Court also said the County “made decisions that are clearly erroneous and acted in an arbitrary manner” and reversed and vacated the decision of the County Board of Appeals.

Which brings us to the present. Why does the County still allow vacation rentals in Ag Districts and will the County carry out the decision of the Board of Appeal. We have no insight and that is a problem. A cornerstone of democratic accountability is requiring elected officials to explain themselves and to give reasons for the actions they take. This has not happened in our case. We have had to endure the abuse of power by the County without knowing why.

The County has faced no consequences for their unlawful behavior. We have had to spend a ton of time and money fighting their illegal behavior. Doesn’t seem fair.

Again, thanks for highlighting this case.